Psychotherapy training: Mentoring for psychotherapists

“To be trained in psychotherapy”, at first, may seem to be something ungraspable. That phrase in itself contains its trap; because it is not something so simple; because how does one train in psychotherapy.

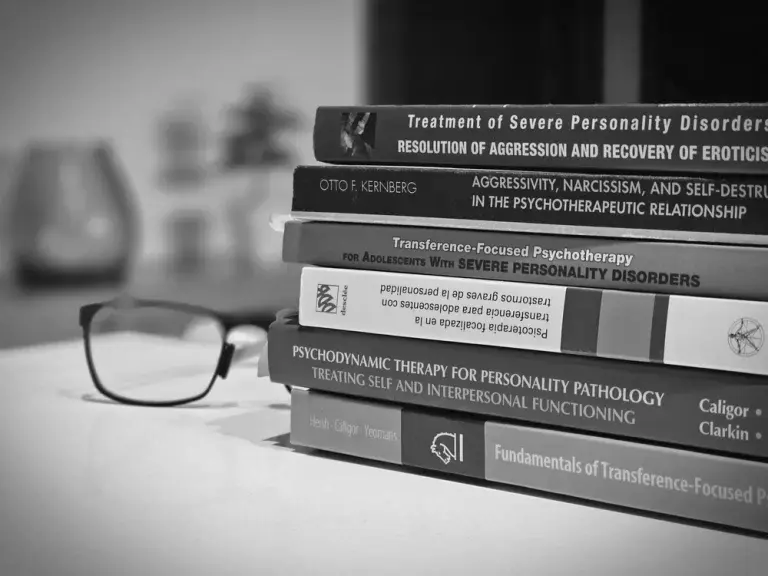

There’s no shortage of courses, exactly. It’s virtually a jungle out there. Given the enormous doctrinal variety, the range of possibilities is overwhelming. And if we add to that the atomization into specific techniques, the confusion can only increase. If you are not clear about where you are and where you want to go, you are lost, despite all your good will. That morass of supply, moreover, is ideal for feeding the pursuit of self-criticism, because there is always another topic, another course, another book missing.

If the image is worth it, the sensation is that of being in front of an open buffet, loaded with options. Always promising, always disappointing. Because it has nothing to do with eating at a good restaurant.

We have all had that feeling at the end of a course, another one, that leaves a poor aftertaste.

What is the problem? It seems that the key starts from the beginning. Training in psychotherapy needs to be, inescapably, theoretical. Even more so in the psychoanalytic orientation, which is particularly rich and deep. It never seems to bottom out. That on the one hand, but on the other hand there remains the question, precisely the most important one, of how to apply what has been learned. How to do this. And here comes the Gordian knot of the matter, even more so in the psychodynamic world, where practical application always remains mired in the mist of mystery, in individual magic. Because, unlike entering an operating room or a consulting room as an observer (where this is always understood as necessary), this is not the case in the world of psychotherapy, and even less so in the psychoanalytic world, due to a multitude of well-known factors.

How to overcome this pitfall? This is where session recording comes in. It is the only way to be the proverbial fly on the wall. I am still surprised by the reticence in this regard, to tell the truth, when we are all surrounded by cameras, when in the end this is part of the office landscape, which does not interfere in the least in the therapeutic process. It is no longer so rare to be able to see sessions in a course.

And is it enough? It’s a lot, certainly, but we should ask for more. This is where the figure of a supervisor/tutor comes in.

Supervision and the interpersonal relationship in mentoring

In the world of psychoanalytic therapy, the importance, the necessity, of supervision has always been taken for granted (without recorded material, of course). Having done personal work and supervision go the same way, that of understanding and managing the movements both within the therapist and in the transference. There is literature, though not much, on how to supervise.

And what is the role of the supervisor/tutor? Of course it has a teaching dimension, but in its interpersonal dimension there is a transcendental aspect that differentiates it from a typical academic relationship.

A tutor is not a teacher. It should not be.

After years of personal experience, I came to the conclusion that the place of the tutor should be that of “holder” of a space for learning. Facilitating and guaranteeing the existence of that space, which in the end will be a space for thinking. A place where curiosity, doubt, and criticism can develop, allowing for growth; growth for both, of course. Through observation and mutual exchange, the student builds and perfects his or her therapist self.

The importance of affect in mentoring for psychotherapists

In general, in life, the learning process is ultimately made on the basis of small modelings, which are determined by the important relationships of our life. In this, the presence of affection (as we well know in TFP) plays a central role, of bonding, in those experiences that will be transforming.

We learn by doing, this is so. But, although experience is the main vehicle in learning, this will be enormously more powerful, its mark more indelible, when it is accompanied or mobilized by affection.

Without reaching Alexander’s “corrective emotional experience”, but not so far away, to learn to do psychotherapy, TFP in particular, we need to study it, see it, do it, and think about it.

Listen, support, create a space to think.

Those of us involved in teaching are not here to pass on certainties. I feel sorry for the new candidates reading this. A few, if any. Love for this work.

What we do do is help to better understand the patient, ourselves, and manage our uncertainties. We facilitate the necessary space for professional and experiential development, so that individuality can be enriched through an intimate yet shared experience.

In the end, the greatest privilege of the mentor is to share the journey with the one being trained. To recognize oneself in the first anxieties and fears; to share the experience of growth, to learn, to re-question ourselves.

In summary

Mentoring is hard work. Sometimes it takes a lot of effort, to be honest. But it is very rewarding. The responsibility is enormous when one stops to think about the importance of this experience, in the future of the therapist.

But usually underneath the great motivations there are also more mundane ones. This is very well explained in a statement made by the Spanish writer and psychiatrist Luis Martín-Santos to an American journalist, who, in an interview in 1962, asked him about his deepest motivations when writing a novel as immense as “Tiempo de silencio”: “What ends do you seek when you write?

And he answered: “To modify the Spanish reality. I also have fun”. So that’s it.